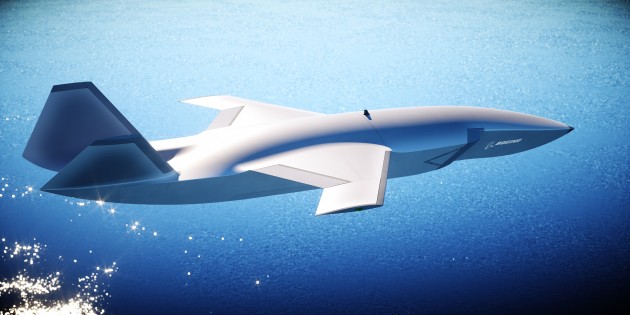

The unveiling of Boeing and RAAF’s experimental unmanned fighter, the Air Power Teaming System (or the less clunky ‘Loyal Wingman’), stole the show at Avalon last week.

The aircraft, developed under Minor Program 6014 Phase 1, is a semi-autonomous air vehicle designed to fight alongside fast jets like the F-35 or F-18. It is capable of carrying weapons, sensors, and possibly EW capabilities. The purpose of the Loyal Wingman is to ‘act as an extension’ of manned platforms, act as a force multiplier, and potentially undertake the riskier missions in a high-end fight. It is controlled from either a manned aircraft or ground stations.

Exact performance details are classified, but according to Boeing, the Wingman can “keep up with the aircraft it is designed to protect” - suggesting the aircraft can match the F-35 for speed, manoeuvrability, signature, and perhaps range (the unclassified range is around 2,000 nautical miles).

Investment figures show that the platform clearly has capability and performance potential: Defence has stumped up $40 million to procure three Wingmen, an unusually large sum for an experimental platform, and the project is the largest investment Boeing has ever made in an unmanned platform outside the US. When asked for exact numbers, a Boeing spokesperson simply said, “Look, we’re Boeing. It’s a lot of money.”

The Wingman, however, raises significant questions about the platform it is designed to protect. It can be flown without an accompanying F-35, although neither RAAF nor Boeing “envision it being used that way”. Why not? If this new unmanned ‘fighter-like’ aircraft with ‘plug and play’ payloads is designed to match the performance and capabilities of an F-35, and can be flown without one nearby, why send an F-35 and a pilot into harm’s way at all? Has the Loyal Wingman made the F-35 obsolete?

These may come as deeply unattractive questions. After all, the F-35 is the world’s most expensive military project. Australia’s first two F-35s only landed in-country three months ago, and another 70 aircraft, worth somewhere in the realm of US$90 million each, are on the way. Yet ADM understands that the Loyal Wingman could be undertaking test flights as early as next year, before RAAF’s F-35s achieve IOC. A lot of money is going into an aircraft whose replacement may have already been unveiled.

So let’s assume that the Loyal Wingman has not made the F-35 obsolete, as Minister for Defence Christopher Pyne asserted when ADM asked the question. That gives us a new question - where is the point of difference?

If the Wingman truly can ‘keep up with an F-35’, then the point of difference must be on-board capabilities rather than flight performance. The air vehicle is far more than glorified ordnance carrier; the project team has taken a modular ‘plug and play’ approach, allowing for quick payload reconfigurations for different missions. This means the point of difference is unlikely to be the on-board capabilities themselves, but rather the number of capabilities the Wingman is capable of carrying in comparison to an F-35 on any given mission.

That conclusion, however, only leads to further questions. Could the combination of Wingmen and an F-35 could be equalled by alternate, unmanned combinations? If ISR, EW, and weapons capabilities are truly ‘plug and play’, perhaps other Wingmen with different on-board configurations, or even a Triton, could fill in for the manned jet. The answer to this question is not clear. Yet as long as there is no clear answer, then the first question – whether the Wingman has made the F-35 obsolete - remains valid.

So let’s take it a step further and assume that the sum of an F-35 and Wingmen truly is greater than any alternate combination of platforms. If the Wingmen are used as intended, the likely scenario will be an F-35 with two Wingmen deployed forward and the pilot out of harm’s way in the rear. Yet this puts strain on the pilot, who now has control, either partial or full, over three rather large aircraft, and relegates the F-35 to an over-the-horizon task manager. Why not assign control of the Wingmen to a ground station or any other manned aircraft? The point of difference that necessitates the presence of an F-35 must now lie between the jet and any other platform capable of acting as a ‘system of systems’ node and remotely tasking an unmanned system, and until that point of difference is clear, the question of obsolescence remains open.

An alternate explanation is that the Wingmen are not actually accompanying the F-35, but the F-35 is the one accompanying the Wingmen. US company Department 13 has demonstrated its ability to take over UAS in flight using protocol mimicry. If RAAF fears that the Wingmen are vulnerable to being commandeered by an adversary, then perhaps the F-35 is actually there to watch the watchmen. This conclusion is abstract, but even if true, it still does not prove the unique utility of F-35s.

Lastly, there is the observation that the F-35 is needed to fill the capability gap between Super Hornets/Growlers and a truly operational fleet of unmanned fighter aircraft. The Loyal Wingman certainly has a fair way to go before it is deployable, but with a test flight scheduled next year, it is well on the way. This observation, therefore, at best relegates the F-35 to the role of a short-lived benchwarmer.

So we’re back where we started – if the Wingman is what it appears to be, why place the person in the cockpit of an F-35 in danger at all? Where is the point of difference? It may be payload capacity, but as long as that conclusion is unclear then the obsolescence question remains valid. If it truly is payload capacity, then the point of difference must lie between the F-35 and any other networked joint platform with ‘system of systems’ integration, beyond line-of-sight and remote tasking capabilities – another unclear conclusion that leaves the original question open. Perhaps an F-35 must fly alongside the Wingman to off-set the vulnerability of the semi-autonomous system, but it is not the only solution to that problem. We’re left with two possible answers: either the Wingman is not what it appears to be, or the F-35 is a short-lived benchwarmer - not quite obsolete, but close.

The question may be deeply uninviting, but until we know more about what the Wingman can and cannot do, it is worth asking.